By: Money Navigator Research Team

Last Reviewed: 19/01/2026

![]() FACT CHECKED

FACT CHECKED

Quick Summary

Source of funds is the “where did this specific money come from?” question. Source of wealth is the “how did the person behind the business build their overall wealth?” question.

Banks ask because UK anti-money laundering rules are risk-based and require firms to understand customers and the reason money is moving through an account, not just the account details.

Requests are often triggered by activity that doesn’t match what the bank currently knows about the business or its beneficial owners, and the practical impact can range from extra questions to temporary limits while a review is completed.

This article is educational and not financial advice.

Source of funds vs source of wealth: the plain-English definitions

Banks and regulators treat “funds” and “wealth” as different concepts. A widely used FCA definition puts it simply:

- Source of wealth describes how total wealth was acquired

- Source of funds refers to the origin of the funds involved in the relationship or transaction (see the FCA’s definition in Financial crime: a guide for firms (PDF)).

Source of funds (SoF): “Where did this money come from?”

In business banking, SoF is usually about a specific inflow/outflow (or pattern of inflows/outflows), for example:

a large inbound transfer

a new revenue stream

a director’s injection of capital

a payout chain (processor > business account > suppliers)

The bank’s core question is whether the provenance of the money makes sense given what it knows about the customer and the transaction.

Source of wealth (SoW): “How did the beneficial owner build their wealth overall?”

SoW is usually about people, not the company account itself: beneficial owners, controllers, sometimes directors. It’s most often used where enhanced checks apply, or where the size of balances/transactions seems inconsistent with what the bank knows.

International standard-setters make the same distinction: the FATF notes that wealth is the customer’s total assets, while funds are the specific assets involved in the relationship/transaction (see FATF guidance on Politically Exposed Persons (PDF)).

Why banks ask businesses for SoF/SoW

Banks ask because their AML/CTF obligations are designed around understanding and monitoring risk over time, not “one-and-done” onboarding.

UK AML rules are set out in the Money Laundering Regulations 2017 (PDF), and industry guidance commonly used by financial services firms (including examples of information that may be relevant, such as expected source of funds and sources of wealth) appears in the JMLSG Guidance Part I (PDF).

At a practical level, SoF/SoW questions tend to serve three operational purposes:

Customer due diligence and “knowing the customer”

Banks build a working picture of what the business does, how it gets paid, and what “normal” looks like.Ongoing monitoring and “does the activity still make sense?”

If activity changes, the bank may refresh its understanding, and SoF/SoW is a common way to test plausibility.Enhanced due diligence in higher-risk cases

Higher-risk customers, sectors, geographies, or ownership profiles can lead to deeper checks, where SoW becomes more central.

Common triggers that lead to SoF/SoW requests

Banks rarely ask because of a single “magic” threshold. More often, a request appears when one or more of these changes occur:

A step-change in value: unusually large or frequent payments compared with prior activity

A step-change in type: new counterparties, new payment rails, new countries

Third-party complexity: money arrives from or is paid to parties not clearly connected to invoicing or contracts

Cash or cash-like patterns: harder-to-audit provenance can prompt deeper questions

Ownership/control changes: new beneficial owners, new controllers, new directors

Mismatch signals: turnover patterns, margins, or transaction descriptions that don’t align with the stated business model

Risk reclassification: policy or sector-wide “de-risking” decisions may increase review frequency

Where reviews escalate, the experience often shifts from “please explain” to “please evidence”, and the operational consequences can look like a compliance review (covered separately in Bank compliance reviews explained).

Summary table

| Scenario | Outcome | Practical impact |

|---|---|---|

| New business receives a one-off high-value inbound transfer | Bank asks for source of funds for that transfer | Payment may be queried; more information may be requested before activity is treated as “normal” |

| Director injects a large sum into the company account | Bank asks for source of funds (and sometimes source of wealth for the director/owner) | Additional evidence may be requested about where the director’s money came from |

| Business begins receiving regular overseas payments | Bank asks for source of funds and may refresh customer profile | More questions on counterparties, contracts, and payment rationale |

| Company balance grows far beyond historic levels | Bank may ask for source of wealth of beneficial owners/controllers | Review may focus on whether overall wealth profile plausibly supports the balances/flows |

| Sudden increase in refunds/chargebacks and reversed settlements | Bank asks for updated explanations and supporting documentation | More friction: increased review, possible temporary limits while risk is reassessed |

What banks typically mean by “evidence” (and why it differs for SoF vs SoW)

“Evidence” is not one fixed checklist. Banks request what helps them connect three things:

the customer profile

the transaction pattern

the claimed origin of money

This is why a SoF request often looks like “show the paperwork for this payment”, while a SoW request looks like “show how overall wealth was built”.

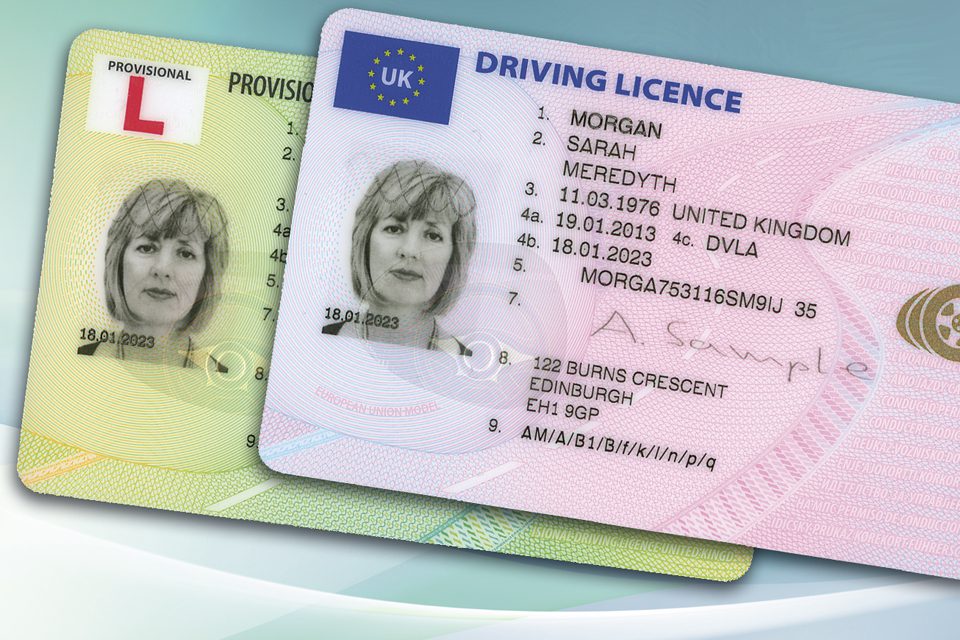

For a broader view of standard onboarding/verification artefacts, see What documents banks check for business bank accounts.

Evidence commonly used for source of funds (transaction-level)

Examples (depending on the nature of the funds):

invoices, contracts, statements of work, purchase orders

settlement reports from platforms/processors and matching bank credits

loan agreements and drawdown confirmations

sale agreements (asset sale, share sale) and completion statements

intercompany documentation for group transfers

bank statements showing the money trail from the originating account

The bank is usually looking for a credible chain from economic activity > payer > payment > business account.

Evidence commonly used for source of wealth (person-level)

Examples (depending on the person and wealth story):

company accounts and dividend records where wealth is business-derived

salary/bonus evidence where wealth is employment-derived

asset sale evidence (for example, property or business sale)

inheritance documentation (where relevant and proportionate)

historic savings/investment records that plausibly explain accumulated assets

The aim is usually not to inventory every asset. It is to establish a reasonable explanation for how the beneficial owner could hold/accumulate wealth at the level implied by account activity (consistent with the SoW/SoF distinction highlighted in FATF PEP guidance (PDF)).

Scenario Table

| Level | What the bank is trying to understand | How SoF/SoW is used | What can change operationally |

|---|---|---|---|

| Scenario-level | “What’s happening that’s different from the expected profile?” | SoF targets the specific inflow/outflow; SoW targets whether overall wealth can plausibly support activity | Customer is re-scored; more monitoring may be applied |

| Process-level | “Can we evidence and document our decision?” | SoF requests tend to be document-matching and traceability; SoW requests tend to be narrative + corroboration | Review queues, follow-up questions, and verification steps increase |

| Outcome-level | “Do we continue, limit, or exit the relationship?” | If the bank can’t get comfortable, it may reduce risk exposure | Temporary limits, declined transactions, or exit decisions become more likely |

The “plausibility test”: why SoF/SoW questions often feel personal

Many businesses experience SoF/SoW requests as an implied accusation. Operationally, they are usually a plausibility test: “Does this activity make sense given what we know?”

That plausibility test often touches commercial realities (turnover, margins, funding structure), which is why banks may ask for clarity even where the business is legitimate. A related discussion of how banks view performance signals appears in Does turnover or profitability matter for a business bank account?.

Why a bank might not explain the trigger in detail

Sometimes banks can explain the request plainly (“we need to understand this payment”). Other times, they communicate in broader terms (“compliance review”, “we need more information”).

One reason is legal sensitivity around suspicious activity reporting and “tipping off”. UK guidance explains that, in certain circumstances, disclosing information that could prejudice an investigation can be an offence (see the discussion of tipping off in Gambling Commission AML guidance). That does not mean a report exists in any given case; it means communication can be constrained.

Compare Business Bank Accounts

Banks and e-money providers can differ in onboarding flow, information requests, and how reviews are handled operationally.

A neutral way to assess options is to compare account features that affect day-to-day running (for example: account type eligibility, payment rails, international payments, support channels, and integration needs).

Browse a broad overview here: Business bank accounts

For a side-by-side example of how providers can differ structurally, see: Tide vs Starling

Frequently Asked Questions

No.

- Source of funds is about the origin of a specific payment or pool of money used in the relationship.

- Source of wealth is about how overall wealth was accumulated, usually by the people who own or control the business.

This distinction matters because the evidence differs. A SoF request often asks for transaction documents (contracts, invoices, settlement reports). A SoW request often asks for information that supports the broader wealth narrative (for example, how assets were built over time).

A request can arise from routine monitoring, periodic refresh cycles, or a change in account behaviour relative to the bank’s current understanding of the business. UK AML obligations are designed to be risk-based and ongoing, not limited to opening the account.

A request also does not, by itself, indicate wrongdoing. It can reflect a documentation gap: the bank may not have enough evidence on file to explain a transaction pattern to its own standards.

In practice, SoW is most often applied to beneficial owners/controllers, because “wealth” is a personal concept (total assets). However, banks can still ask questions about the company’s funding structure and capital sources, especially where owners fund the business directly.

SoF is more directly tied to the company account’s transactions. If a director injects funds, the bank may ask SoF for that transfer and (depending on risk) SoW for the director/owner to understand how the director could plausibly hold that level of funds.

It depends on what the funds represent. Evidence typically aims to show a credible link from economic activity (or a legitimate event like a sale or loan) to the payer/source account, and then into the business account.

For trading income, banks often look for contract/invoice support and matching settlement trails. For loans, they often look for loan documentation and drawdown proof. For asset sales, they often look for completion statements or sale contracts plus the banking trail.

Banks may still ask questions because “another account” doesn’t explain the original provenance of the money. A SoF question typically looks beyond the immediate sending account to the underlying origin (for example: trading receipts, savings, loan proceeds, sale proceeds).

Where owners move money between personal and business accounts, banks can also ask whether the movement aligns with the declared business model and expected funding structure.

Cross-border payments can introduce extra complexity: different counterparties, different legal jurisdictions, and reduced visibility into underlying commercial context. Banks may therefore need more information to reach the same comfort level as they would for simple domestic flows.

This is not limited to “high-risk countries”. Even normal international trade can require more documentary linkage (contracts, shipping/service delivery evidence, platform settlement trails) to establish SoF clearly.

Yes, operationally this can happen. Restrictions can be partial (limits on certain payment types) or broader (a pause while information is reviewed), depending on the bank’s internal risk appetite and what information is outstanding.

Where this occurs, it often follows the same practical pattern as a compliance review: the bank asks for information, and account functionality may change until the review is resolved.

Sometimes banks can give a straightforward explanation (“we need to understand this payment”). In other cases, communication is limited because sharing specific suspicions can be legally sensitive, particularly around “tipping off” concepts in UK AML enforcement.

Guidance for regulated sectors discusses circumstances in which disclosures can prejudice investigations and therefore become offences (see Gambling Commission AML guidance on tipping off). This does not confirm any report exists in a particular case; it explains why banks may stay general.

There is no single standard timeframe. Timelines vary based on the complexity of the activity, how many parties are involved, whether information arrives in stages, and the bank’s internal queues and escalation steps.

Some requests resolve quickly where documentation is clear and matches the transaction trail. Others take longer where funds flow through multiple entities, where historic wealth narratives are involved, or where additional checks are triggered by inconsistencies.

Outcomes typically move along a spectrum: more questions, tighter monitoring, limits on certain activity types, or an exit decision. The key point is that the bank’s decision is usually framed as a risk decision under its AML obligations rather than a judgement on the business’s commercial quality.

Where an exit decision is being considered, banks often request a broader package of documents and clarifications. A detailed, separate guide to that document set is here: Documents banks ask for when considering account closure.

SoF vs SoW requests are best understood as a coherence check in a risk-based system. Banks are trying to make the story of the account internally consistent: the business model, the counterparties, the transaction size/frequency, and the people behind the company should “fit together” well enough that ongoing monitoring doesn’t produce unresolved anomalies.

That is why “proof” and “truth” can feel misaligned with the experience. The process is less like a courtroom standard and more like an operational decision: whether the bank can document a reasonable understanding of why this money is here and why this customer plausibly has it, using the concepts and distinctions described in FCA and FATF guidance.

Sources & References

Financial Conduct Authority – Financial crime: a guide for firms (PS11/15) (PDF)

Joint Money Laundering Steering Group – Guidance Part I (June 2023, July revision) (PDF)

UK Government – Money Laundering Regulations 2017 (SI 2017/692) (PDF)

HMRC – Economic Crime Supervision Handbook: overview of MLR 2017

Gambling Commission – AML guidance on tipping off and prejudicing an investigation